‘The Farrier in the Fray’, The War Illustrated, 25th September 1914. Reproduced with the permission of Time Inc. UK.

The War Illustrated emerged in 1914 as an illustrated newspaper dedicated solely to coverage of events during the First World War. Unlike the established broadsheets, The War Illustrated was affordable and targeted at the ‘busy’ reader. Packed with illustrations and photographs, and with dramatic stories of bravery and excitement, readers were able to follow events as they unfolded week-by-week. This gave more people in Britain access to written news about the War’s progress, but also to illustrated and photographic images of what war looked like – and portrayals of soldiers and horses were prominent in this coverage.

Publications like The War Illustrated brought news of The Great War into the home. The war illustrators provided visually entertaining images of major battles, of acts of heroism and of moments of drama and pathos. Increasingly, however, photographs were also used and, while it was difficult to capture the action as it happened, photographers were able to capture the aftermath of battles and scenes of life behind the lines.

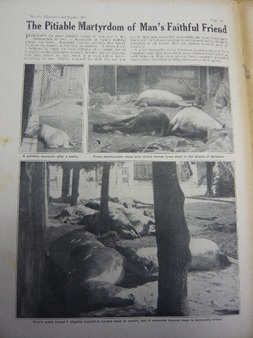

For example, in October 1914 The War Illustrated published a full-page article depicting ‘The Pitiable Martyrdom of Man’s Faithful Friend’. The greater part of the page was given over to three photographs showing a large number of dead horses lying in the streets of Soissons. Most lay stretched out, but in one of the photographs a light coloured horse appeared almost to have crumpled to the ground. Every horse had been stripped of any harness and equipment; their nakedness almost emphasising the ‘martyrdom’ of the animals who had been drawn into a war beyond their comprehension.

The article would have had a powerful effect on contemporary audiences. Readers of The War Illustrated had been brought up in an era where portrayals of the horse in battle were often used to safely convey war’s realities; a rider-less horse inviting the audience to wonder what had happened to its rider, or dead horses and debris conveying the intensity of a battle. Indeed, the wounded or dying horse, the rider-less horse alone in No Man’s Land, the dead horse, or the horse standing patiently over the recumbent figure of his sleeping (or deceased) master were inherited images of battle which carried with them the assumption that horses were part of this landscape.

“Perhaps the most pitiable aspect of the war is the destruction in tens of thousands of man’s faithful friend – the horse. Innocent, trustful, nervous, it is forced to assist its master in fighting his battles. … A great sympathy exists between cavalrymen and their chargers, and there have been many instances of horsemen with tears in their eyes, giving their wounded animals a fond caress, and then putting them out of their agony”.

‘The Pitiable Martyrdom of Man’s Faithful Friend’, The War Illustrated, 3rd October 1914. Reproduced with the permission of Time Inc. UK.

The particularly emotive nature of this article had the potential to shock, and especially if the horses pictured were imagined to be British horses ‘combed … out from happy silences on thymey downs’.[1] Even with its limitations, photography brought warfare closer to the reader than the war illustrators (for all their flair and imagination) had been able to do before. Indeed, had the ‘pitiable martyrdom’ portrayed dead soldiers rather than his ‘faithful friend’ it is safe to assume this would have stepped over the line of what was acceptable. Certainly, any explosion that had the energy to stop a horse in its tracks would have had a devastating effect on the far more fragile body of a man, and this implied comparison no doubt came quite close enough. Readers of The War Illustrated did not want to be forced to imagine the shattered bodies of their loved ones. Rather, it was the horse who often enabled the British public to imagine these dark realities of war from a safe distance. There was certainly reassurance to be found in the soldier’s sympathy for the horse’s plight.

What was and was not shown was important for morale, but this was not simply a matter of propaganda. In fact, what was and was not said was decided as much by the people who bought the newspapers as it was by those who produced them. Publications like The War Illustrated reflected the tastes and views of their readership, and this in turn encouraged the type of coverage that was produced.[2] Indeed, as the war progressed and public feeling shifted, The War Illustrated adapted its coverage to suit the mood of its readers.

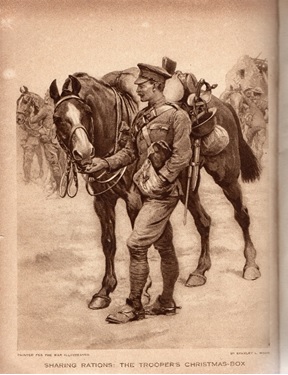

Wood S.L., ‘Sharing Rations: The Trooper’s Christmas Box’, The War Illustrated, supplement to Christmas edition, 23rd December 1916. Reproduced with the permission of Time Inc. UK.

Increasingly, its photographs and illustrations conveyed the human, and humane, face of the War. For example, the 1916 Christmas edition of The War Illustrated carried on its front page an illustration by Stanley Wood. It depicted a trooper smiling kindly as he shared his precious ‘Christmas Box’ with his horse. This scene offered consolation at a time of year when separation from loved ones would have been felt all the more keenly. It reassured the British public by allowing them to imagine a soldier who was humane, kind and who was able to find friendship and moments of happiness even amidst the almost unimaginable horror of war. The War Illustrated provided comfort at a time when it was most needed. Through its photographs and illustrations it helped to bring the War, and those it had separated from friends and loved ones, closer to home.

[1] Jeudwine G.M., ‘War-Horses’, in Galtrey S., The Horse and the War, Country Life, London, 1918, p.12.

[2] Wilkinson G.R., Depictions and Images of War in Edwardian Newspapers, 1899-1914, Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2003, p.xi.

Biography

This blog was written by Dr Jane Flynn. Jane was awarded a PhD by The University of Derby in 2016 for her thesis entitled, Sense and Sentimentality: The Soldier-Horse Relationship in The Great War. Jane is a teacher, book restorer and writer with research interests in myth, memory and horse-human interactions in work and war. Jane blogs on janeflynn-senseandsentimentality.com and hosts the Facebook group ‘Horses and History’.

Reblogged this on Sense and Sentimentality.

LikeLike